Lake Tanganyika, an ancient lake in the Western Rift of the African Great Rift Valley, is the largest Rift lake and second largest by surface area, as well as being the deepest and holding the greatest water volume among African lakes. It also is the second largest (volume), deepest and longest freshwater lake in the world. It is located on a line dividing the eastern and western Africa floral regions, being one of the richest freshwater ecosystems in the world, and home to more than 2,000 plant and animal species, about 600 species endemic to its watershed. Although an estimated 25–40 percent of the protein in the diets of the one million people living around the lake comes from lake fish, unregulated large-scale commercial fishing has depleted the lake’s fish resources. There also is evidence that climate change and related factors are shrinking fish and algae populations. Thus, its current environmental and management challenges should be reviewed prior to considering any GEF-catalyzed management interventions.

| TWAP Regional Designation | Eastern & Southern Africa; Western & Middle Africa | Lake Basin Population (2010) | 13,754,496 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| River Basin | Congo | Lake Basin Population Density (2010; # km-2) |

57.7 | |

| Riparian Countries | Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Zambia | Average Basin Precipitation (mm yr-1) |

1,048 | |

| Basin Area (km2) | 194,317 | Shoreline Length (km) | 2,530 | |

| Lake Area (km2) | 32,685 | Human Development Index (HDI) | 0.4 | |

| Lake Area:Lake Basin Ratio | 0.138 | International Treaties/Agreements Identifying Lake | Yes |

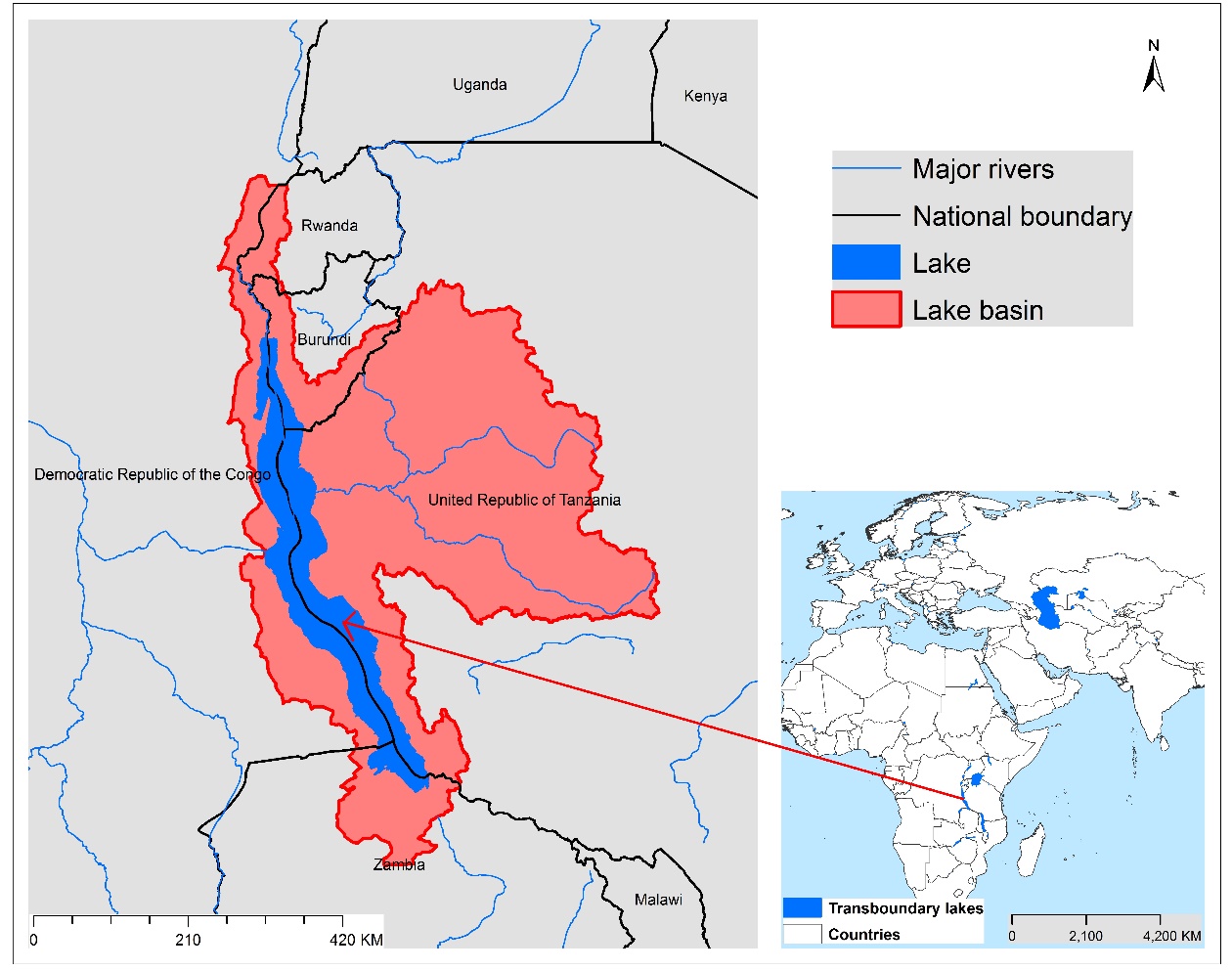

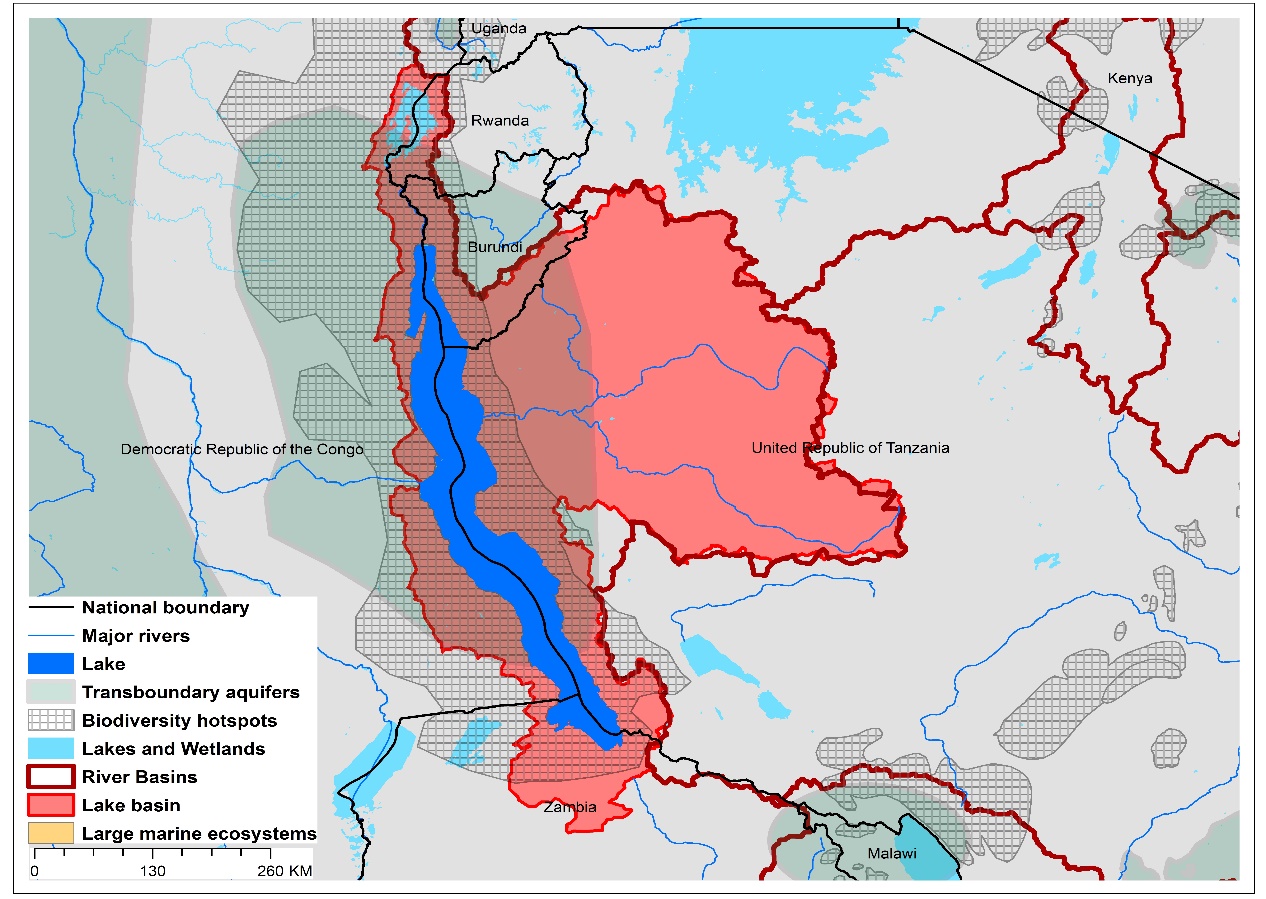

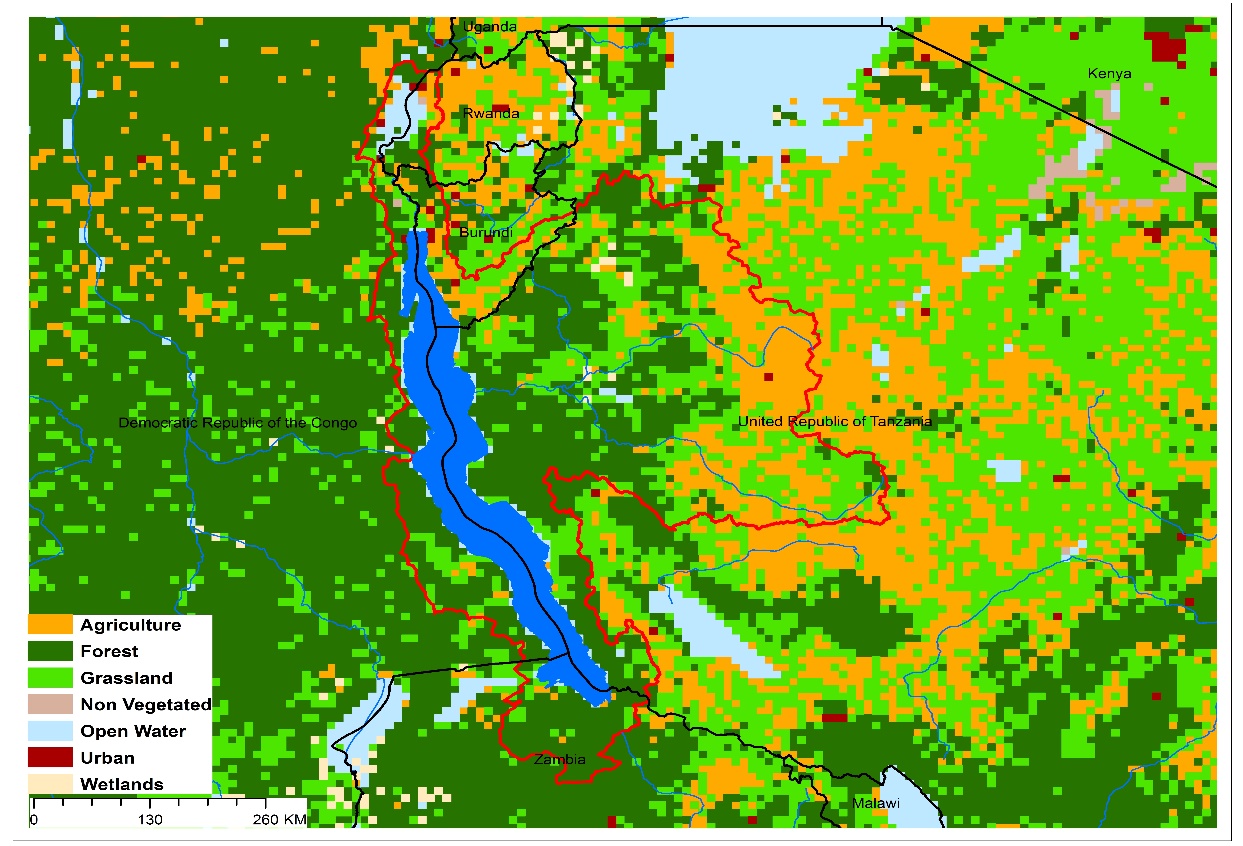

Lake Tanganyika Basin Characteristics

(a)Lake Tanganyika basin and associated transboundary water systems

(b)Lake Tanganyika basin land use

A serious lack of global-scale uniform data on the TWAP transboundary in-lake conditions required their potential threat risks be estimated on the basis of the characteristics of their drainage basins, rather than in-lake conditions. Using basin characteristics to rank transboundary lake threats precludes consideration of the unique features that can buffer their in-lake responses to basin-derived disturbances, including an integrating nature for all inputs, long water retention times, and complex, non-linear response dynamics.

The lake threat ranks were calculated with a spreadsheet-based interactive scenario analysis program, incorporating data and information about the nature and magnitude of their basin-derived stresses, and their possible impacts on the sustainability of their ecosystem services. These descriptive data for Lake Tanganyika and the other transboundary lakes included lake and basin areas, population numbers and densities, areal extent of basin stressors on the lake, data grid size, and other components considered important from the perspective of the user of the data results. The scenario analysis program also provides a means to define the appropriate context and preconditions for interpreting the ranking results.

The Lake Tanganyika threat ranks are expressed in terms of the Adjusted Human Water Security (Adj-HWS) threats, Reverse Biodiversity (RvBD) threats, and the Human Development Index (HDI) score, as well as combinations of these indices. However, it is emphasized that, being based on specific characteristics and assumptions regarding Lake Tanganyika and its basin characteristics, the calculated threat scores represent only one possible set of lake threat rankings. Defining the appropriate context and preconditions for interpreting the lake rankings remains an important responsibility of those using the threat ranking results, including lake managers and decision-makers.

(Estimated risks: red – highest; orange – moderately high; yellow – medium;

green – moderately low; blue – low)

| Adjusted Human Water Security (Adj-HWS) ThreatScore |

Relative Adj-HWS Threat Rank | Reverse Biodiversity (RvBD) Threat Score | Relative RvBD Threat Rank | Human Development Index (HDI) Score | Relative HDI Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.84 | 27 | 0.71 | 6 | 0.40 | 8 |

It is emphasized that the Lake Tanganyika rankings above are discussed here within the context of the management and decision-making process, rather than as strict numerical ranks. Based on its geographic, population and socioeconomic assumptions used in the scenario analysis program, the calculated Adj-HWS score for Lake Tanganyika indicates a medium threat rank compared to other priority transboundary lakes.

The Reverse Biodiversity (RvBD) for Lake Tanganyika, which is meant to describe its biodiversity sensitivity to basin-derived degradation, places the lake in a high threat rank, compared to the other transboundary lakes. Management interventions directed to improving the biodiversity status must be viewed with caution, however, since we lack sufficient knowledge and experience to accurately predict the ultimate impacts of biodiversity manipulations and preservation efforts. Further, the RvBD scores indicate the relative sensitivity of a lake basin to human activities, and high threat scores per se do not necessarily justify management interventions. Such interventions may actually increase biodiversity degradation, noting that many developed countries have already fundamentally degraded their biodiversity because of economic development activities. Thus, activities undertaken to address the Adj-HWS threats may actually degrade the biodiversity status and resources, even if the health and socioeconomic conditions of the lake basin stakeholders are improved as a result of better conditions, thereby increasing stakeholder resource consumption.

The relative Human Development Index (HDI) places the Lake Tanganyika basin in the upper quarter of the priority transboundary lake basins in regard to its health, educational and economic conditions.

(Scores for Adj-HWS, RvBD and HDI ranks are presented in Table 1; the ranks may differ in some cases because of rounding of figures; Estimated risks: red – highest; orange – moderately high; yellow – medium;

green – moderately low; blue – low)

| Adj-HWS Rank | HDI Rank | RvBD Rank | Sum Adj-HWS + RvBD | Relative Threat Rank |

Sum Adj-HWS + HDI | Relative Threat Rank | Sum Adj-HWS + RvBD + HDI | Overall Threat Rank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | 8 | 6 | 32 | 14 | 34 | 17 | 40 | 10 |

When multiple ranking criteria are considered together in the threat rank calculations, the Adj-HWS and HDI scores considered together place Lake Tanganyika in the upper third of the threat ranks. The relative threat is slightly increased when the Adj-HWS and RvBD threats are considered together. Considering all three ranking criteria together, Lake Tanganyika exhibits a high threat ranking.

Further, a series of parametric sensitivity analyses of the ranking results also was performed to determine the effects of changing the importance of specific criteria on the relative transboundary lake rankings. This analysis involved increasing or decreasing the weights applied to the threat ranks derived from multiple ranking criteria to reassess the relative impacts of the weight combinations on the threat ranks. For example, in determining the sensitivity of the Adjusted Human Water Security (Adj-HWS) and Biodiversity (BD) ranking criteria, the threat rank associated with the first was assumed to be of complete (100%) importance (i.e., rank weight of 1.0), while the other was assumed to be of no (0%) importance (i.e., rank weight of 0.0). The relative importance of the two ranking criteria was then successively changed, with weight combinations of 0.9 and 0.1, 0.8 and 0.2, etc., until the first ranking criteria (Adj-HWS) was assumed to be of no importance (rank weight of 0.0) and the second (BD) was of complete importance (rank weight of 1.0). In the case of Lake Tanganyika, the 0.5 and 0.5 weight combinations for three cases of parametric analysis for Lake Tanganyika resulted in respective threat rankings of 21st, 18th and 21st, respectively, among the total of 23 African transboundary lakes in the TWAP study (see Technical Report, Section 4.3.3, pp44-49).

In essence, therefore, identifying potential management intervention needs for Lake Tanganyika must be considered on the basis of both educated judgement and accurate representations of its situation. A fundamental question to be addressed, therefore, is how can one decide that a given management intervention will produce the greatest benefit(s) for the greatest number of people in the Lake Tanganyika basin? Accurate answers to such questions for Lake Tanganyika, and other transboundary lakes, will require a case-by-case assessment approach that considers the specific lake situation and context, the anticipated improvements from specific management interventions, and its interactions with water systems to which the lake is linked. To this end, it is noted that the African transboundary lakes as a group merit special attention in regard to management interventions, with some lakes requiring more immediate attention than others.